An Erroneous View of First-Century Judaism's Use of Parables

As we have studied in detail elsewhere, Judaism commonly used parables (Hebrew: mashal) to take complex ideas and distill them into a simple narrative in order to illustrate a point rather than conceal it. This means that the general message of the parable would have been easily understood by those who heard it. Messiah's use of the parable of the prodigal son was not some kind of secret code but the easiest way to deliver His message to His Jewish audience.

As we have studied in detail elsewhere, Judaism commonly used parables (Hebrew: mashal) to take complex ideas and distill them into a simple narrative in order to illustrate a point rather than conceal it. This means that the general message of the parable would have been easily understood by those who heard it. Messiah's use of the parable of the prodigal son was not some kind of secret code but the easiest way to deliver His message to His Jewish audience.

The author of the booklet notes,

The scribes and Pharisees- the religious leaders of Jesus' day- surely expected the prodigal son's father to drop the hammer hard on the wayward youth. One thing they were certain of: there could be no instant forgiveness. Nor was the prodigal likely to merit full reconciliation with his father, ever. Surely he would have to take his medicine in full doses.

Here we must again briefly note that the author has expressed an inaccurate view of the first century: the scribes and the Pharisees had little power during the lifetime of Messiah. Far greater power was wielded by the Sadducees (the Levites and chief priests) who controlled access to and worship in the Temple. As noted by Jaroslav Jan Pelikan:

To the degree that any of these parties had power, however, it belonged to the Sadducees. More precisely, the aristocratic priests and a few prominent laymen had power and authority in Jerusalem; of the aristocrats who belonged to one of the parties, most were Sadducees. According to the Acts of the Apostles (5:17), those who were around the high priest Caiaphas were Sadducees, which recalls the evidence of the Jewish priestly aristocrat, historian, and Pharisee Josephus.1

Next, the author of the booklet paints every scribe and Pharisee with a broad brush and presumes a hard-heartedness among them that is inconceivable for most parents. This hard-heartedness is the exact opposite of what Messiah knew to be true of His kinsmen:

"If you then, being evil, know how to give good gifts to your children, how much more will your heavenly Father give the Holy Spirit to those who ask Him?" (Luke 11:13)

Further, the author of the booklet takes the parable of the prodigal son out of its context. Two other parables (the parable of the lost sheep and the parable of the lost coin) precede the parable of the prodigal establishing the tenor, tone, and topic of Messiah's message.

So He told them this parable, saying, "What man among you, if he has a hundred sheep and has lost one of them, does not leave the ninety-nine in the 1open pasture and go after the one which is lost until he finds it? When he has found it, he lays it on his shoulders, rejoicing. And when he comes home, he calls together his friends and his neighbors, saying to them, 'Rejoice with me, for I have found my sheep which was lost!' I tell you that in the same way, there will be more joy in heaven over one sinner who repents than over ninety-nine righteous persons who need no repentance. (Luke 15:3-7)

"Or what woman, if she has ten silver coins and loses one coin, does not light a lamp and sweep the house and search carefully until she finds it? When she has found it, she calls together her friends and neighbors, saying, 'Rejoice with me, for I have found the coin which I had lost!' In the same way, I tell you, there is joy in the presence of the angels of God over one sinner who repents." (Luke 15:8-10)

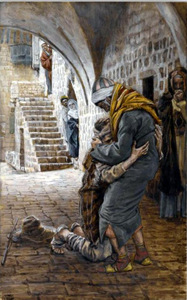

Following "the parable of the lost sheep" and "the parable of the lost coin", we find what could reasonably be called "the parable of the lost son".

There is a consistent thread of meaning delivered via these parables:

| The Lost Sheep | The Lost Coin | The Lost Son | Symbolic Meaning |

| The shepherd | The woman | The father | Messiah |

| The flock | The coins | The sons | The nation of Israel |

| The lost sheep | The lost coin | The lost son | Sinners in Israel |

| The 99 sheep | The 9 coins | The loyal son | The faithful in Israel |

| The sheep's return | The coin's recovery | The son's return | A repentant sinner |

| Rejoicing shepherd | Rejoicing woman | Rejoicing father | A rejoicing G-d |

| The message: Messiah came to bring about repentance among sinners. | |||

In the first two parables, we see the owners of the sheep and the coin going and seeking after that which is lost. In the last parable, we see the repentant son seeking to humble himself before his father: it is a more proactive approach being demonstrated in the story.

Finally, the author of the booklet ascribes false attributes to the loyal son in the parable:

As this parable of Jesus continues, it becomes obvious that the second (and opposite) kind of sinner is epitomized by the elder brother. This young man is an emblem of all the seemingly honorable, superficially moral, or outwardly religious sinners- people just like the scribe and the Pharisees. Here is a sinner who thinks he can cloak his inner rebellion with outward righteousness.

Nowhere in Messiah's delivery of the parable is anything stated to imply the older son is "seemingly honorable, superficially moral, or outwardly religious". The only issue described by the parable is the elder son's hard-heartedness towards the genuine repentance of his younger brother. And that issue is the heart of Messiah's message.

Let's tie all of this together with a little more context from the beginning of Luke chapter 15:

Now all the tax collectors and the sinners were coming near Him to listen to Him. Both the Pharisees and the scribes began to grumble, saying, "This man receives sinners and eats with them." (Luke 15:1-2)

These three parables were delivered by Messiah in response to the grumbling of the Pharisees and scribes. He informed them in clear terms that:

- His job was to bring about repentance among the sinners of Israel.

- His job was not to teach those who were already righteous.

- They, like the older brother in the parable, should not have hard hearts towards their sinful "younger brothers" among the people of Israel.

Having noted of all this, let's summarize the point.

Parables (Hebrew: mashal) were used by Jewish rabbis to communicate a specific message to a Jewish audience. If someone takes the message out of its context or imports false assumptions into the parable then the conclusions they draw about its message will also be erroneous. Like Haeckel, their bad assumptions will lead to bad conclusions.

Let’s reject flawed and ahistorical interpretations of Messiah's parables and press on to the Truth. As Messiah declared, He is "the Way and the Truth and the Life."

<><